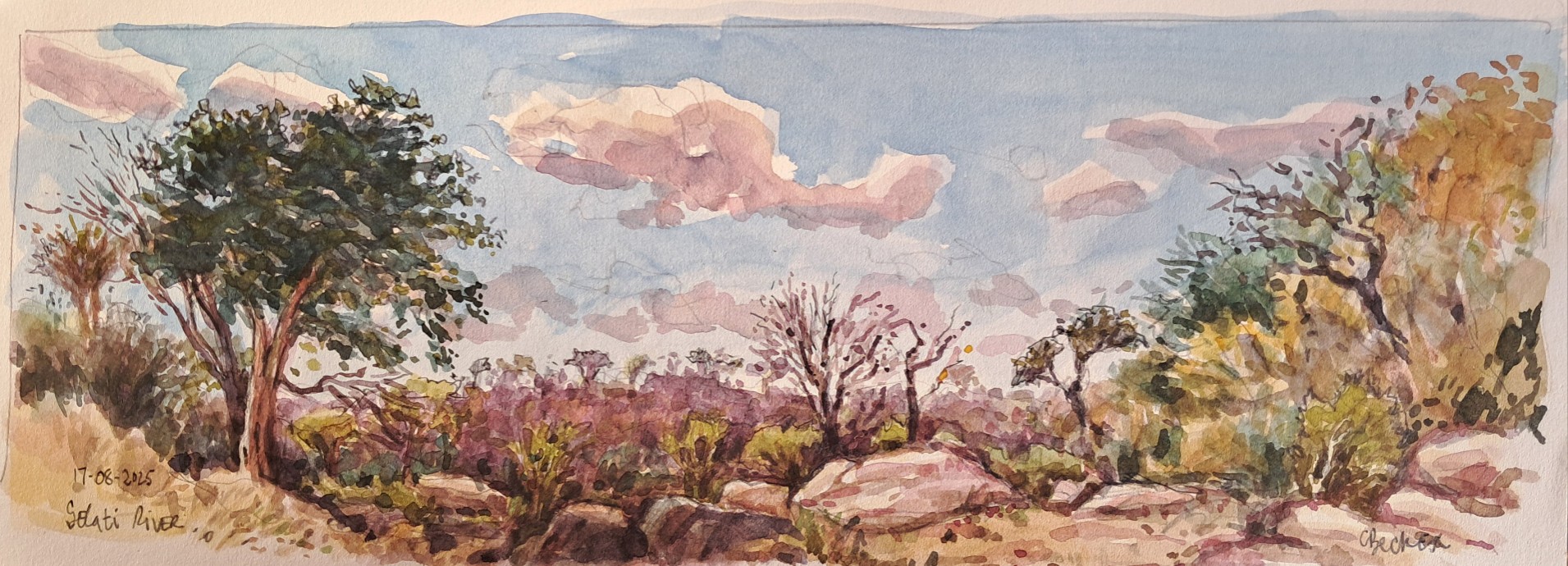

By a stroke of good fortune, I’ve again escaped the dank and stormy Western Cape. I’m in the Selati Nature Reserve, not that far from the Kruger Park. Right below our lodge runs the Selati River. OK, it’s not exactly running – but there are large pools of water just below the lodge, and these are often visited by Kudu, Impala, small antelope and many birds. The bushveld in winter is another story – perfectly warm windless days, followed by cool, crisp nights around the fire. The beautiful Nyala are almost tame and spend their days browsing around the lodge. They will obligingly linger long enough for a quick sketch.

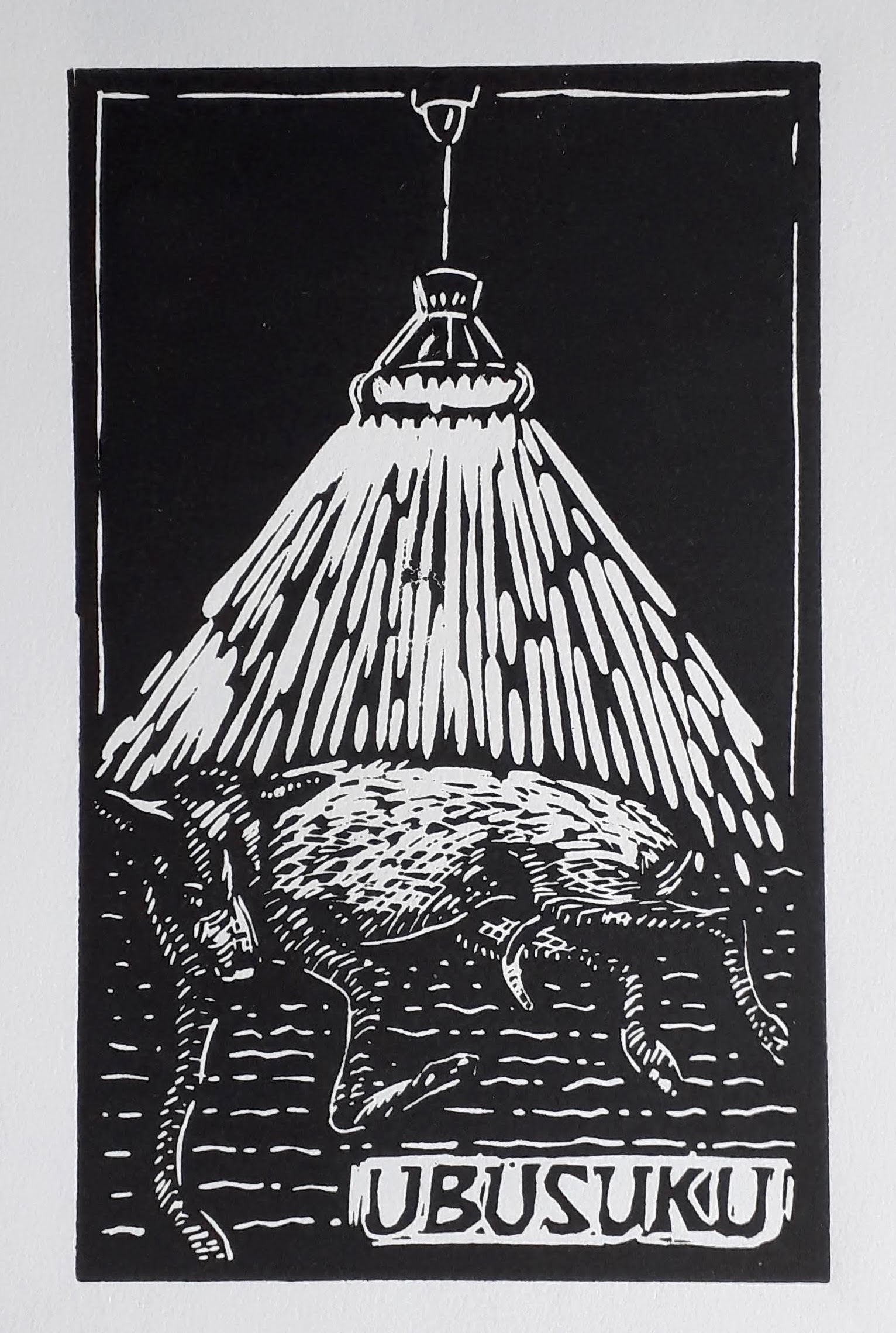

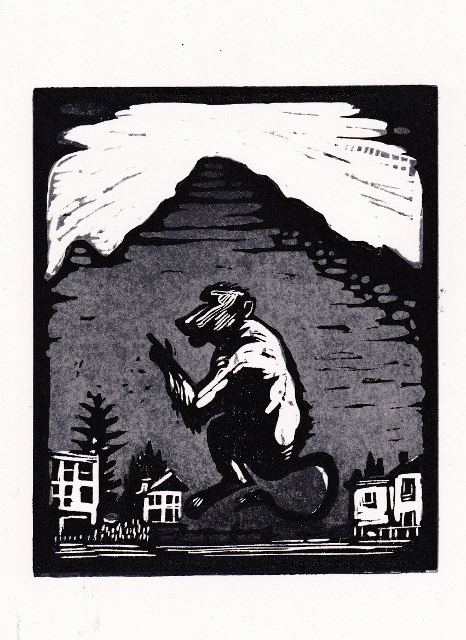

Our lodge isn’t fenced, meaning, yes, we could cross paths with wandering predators or ruminants at any time. Crossing the lawn at night we feel a primitive frisson of fear. Things are rustling in the undergrowth, and we can hear the throaty cough of a lion. Sound carries far in the still night air, but how far away is it, exactly? Are we being watched? Are we being crept up on? In the enveloping darkness we stare into the hardwood coals of the bushveld braai fire just like our ancestors did, frequently scanning the perimeter for yellow eyes. We’re comfortable but, like those ancestors, aware that something just might be seeing us as food. We find ourselves in a relaxed but ready equilibrium, and it feels good.

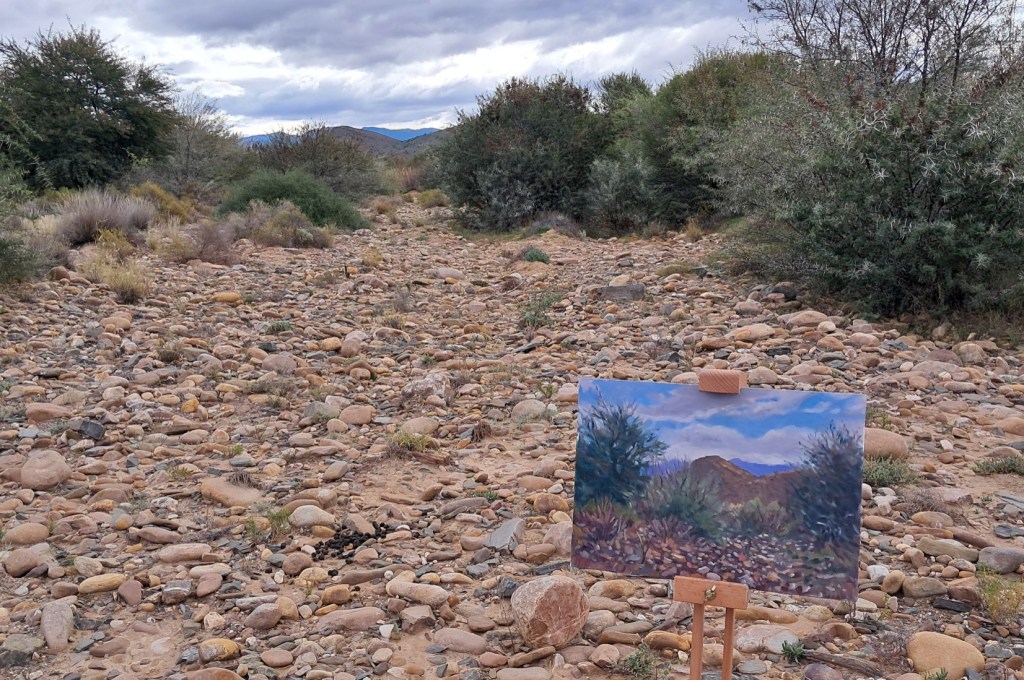

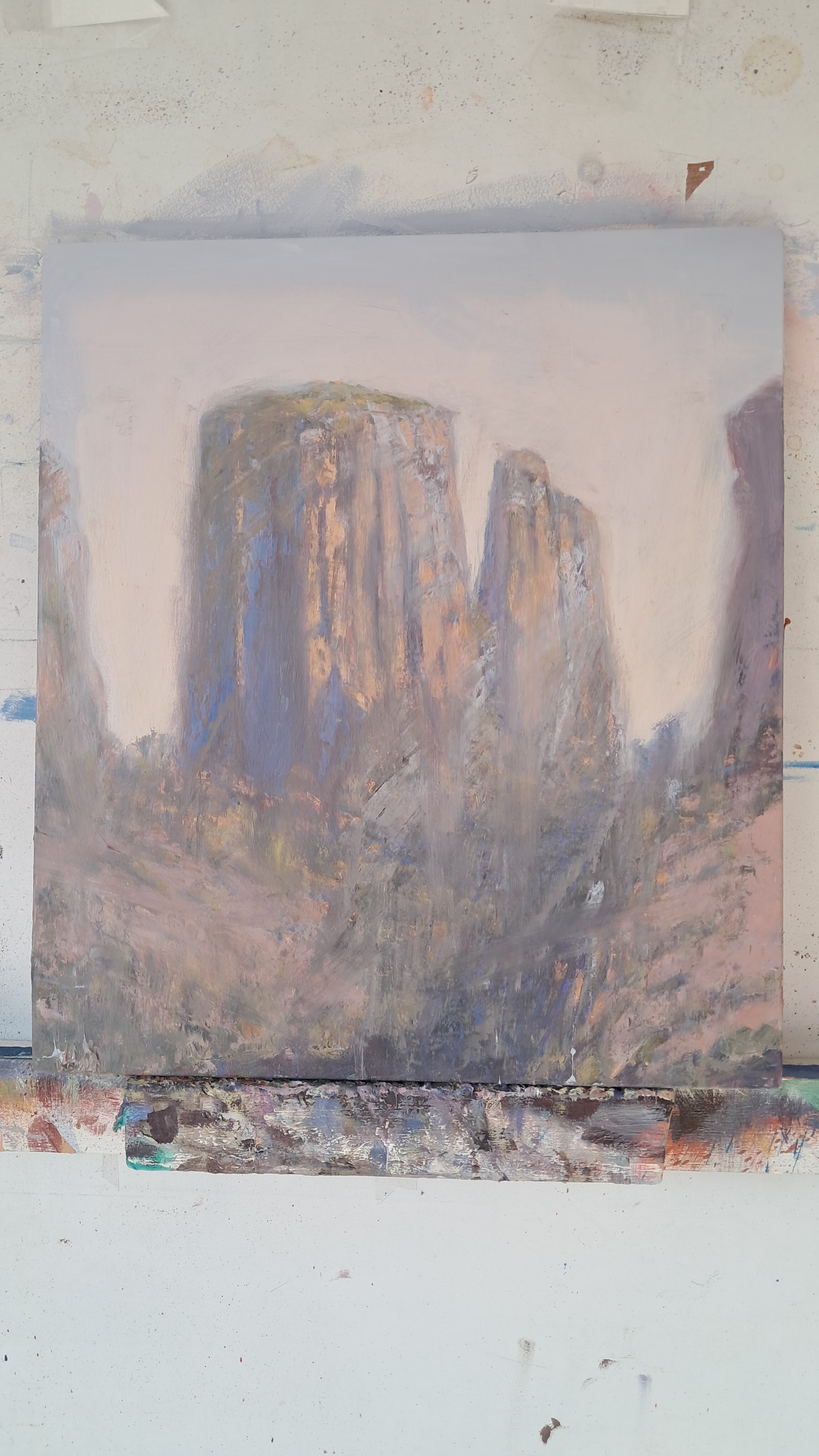

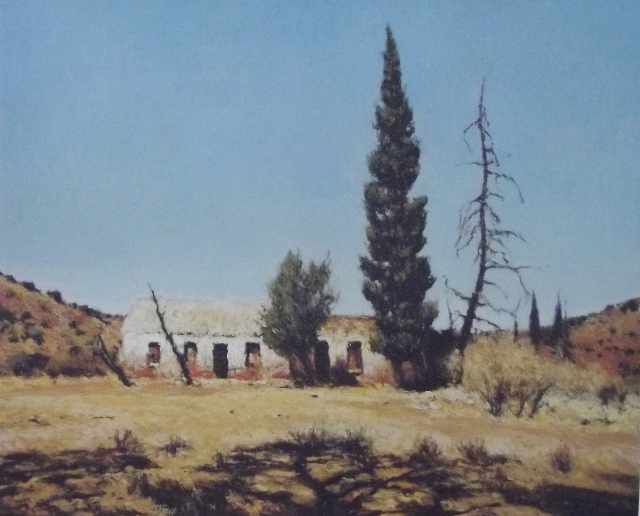

In the morning I wander down to the riverbed. The dryness of the earth is astounding, brittle grasses crunching underfoot. The colouration – mainly siennas and ochres – is right up my street. Fragrances of dung drift up from the warming earth. I’ve got watercolours and a small chair, and I set up on one of those huge granite boulders. There are intermittent shallow pools of water here and a kingfisher hovers and dives. Are there really fish in those pools? What is he catching? I know so little! Up river I see Impala and furtive Kudu flitting in and out of the shadows of the yellow Mopani trees. Could there be a better place than this? I paint because the slow, focussed, meditative act of painting is the best way I know to connect with this old world. But even in Arcadia things can go wrong, starting with dehydration and sunburn, and ending like this:

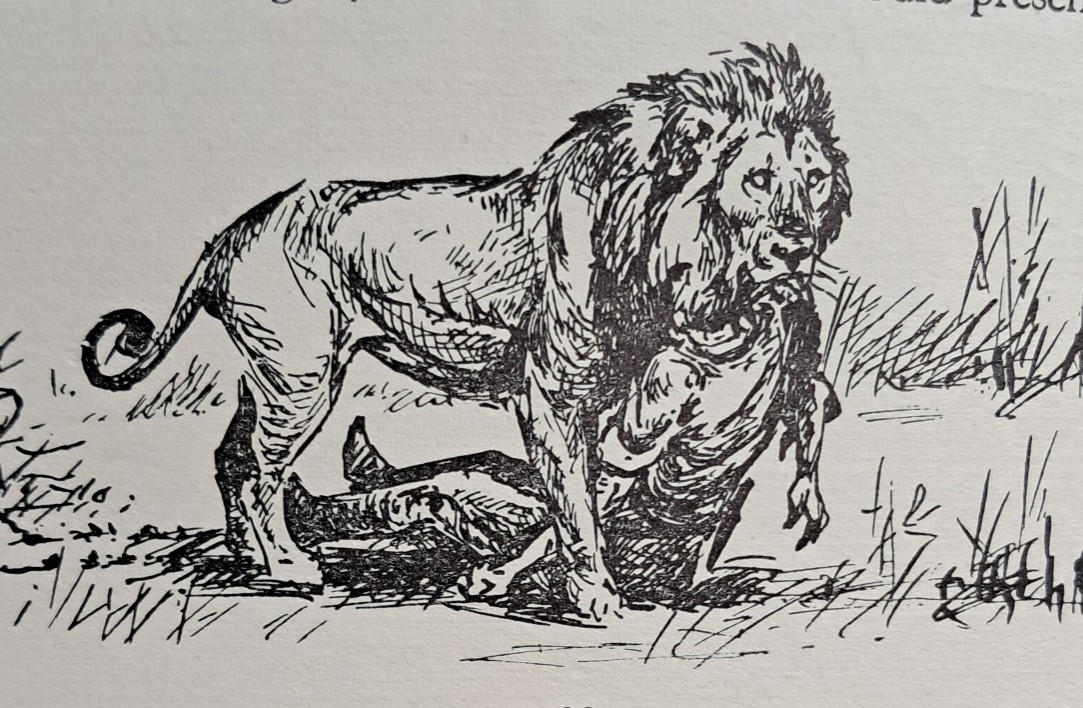

Incidentally, there are at least two survivors of lion attacks who lived to tell the tale. The steely and evangelical David Livingstone was one. He felt no pain, and reasoned that the shock of the attack had put him into a state where he could observe but didn’t feel. He hoped, he said, that all prey died in that state.

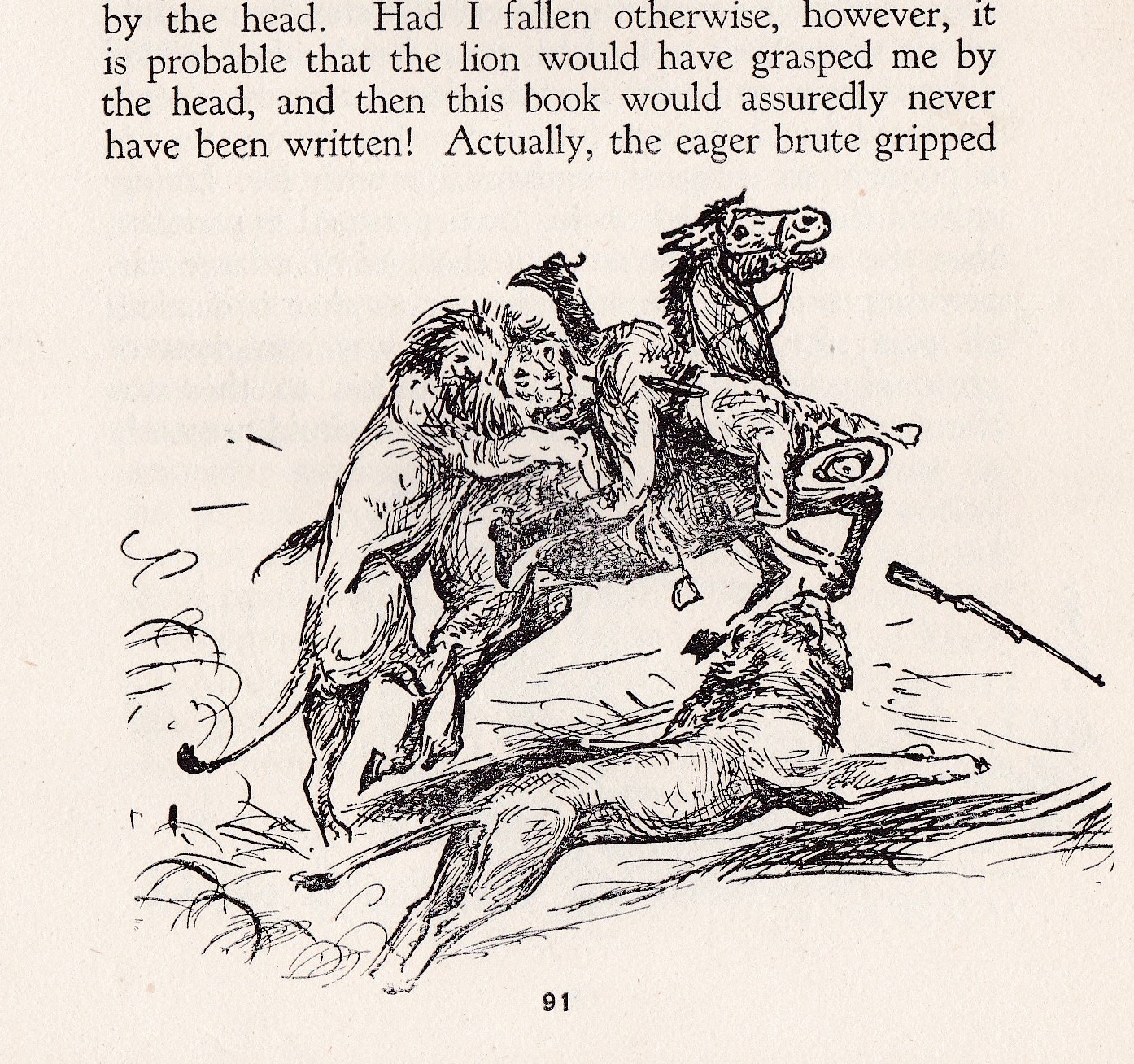

“I certainly was in a position to disagree emphatically with Dr Livingstone,” said Harry Wolhuter, one of the first game wardens at the Kruger Park. Wolhuter had been pulled off his horse, and the lion was dragging him along by the shoulder. “As the lion was walking over me, his claws would rip wounds in my arms…I was conscious of great physical agony; and in addition to this was the mental agony as to what the lion would presently do with me.” He had his sheath knife with him, and he managed to stab the lion in the heart. Then, in excruciating pain, he clambered one -armed up a tree and, ready to pass out from loss of blood, strapped himself to it. There were two lions, you see, and before long the other lion was hungrily eyeing him too. Eventually help arrived, and the next day, unable to walk, he was portered through the bush to Komatipoort hospital, a mere five day journey on foot. The pain and sepsis must have been incredible, but Hardy Harry survived this ordeal with all his limbs intact.

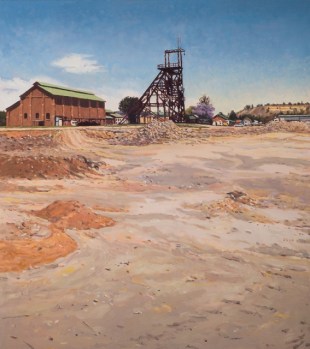

In the course of his duties, Harry Wolhuter shot a lot of lions. This seems strange – even shocking – to us, but in the early days of the park, there were very few antelope. The game had all been shot out by hunting, not to mention hungry Boer Commandos during the Anglo – Boer war. The only way to get the numbers up was to thin out the predators. So the lions, leopards and wild dogs had to go.

The wild I am seeing now looks primordial, the way it has always been and should remain. It is easy to forget that earlier generations saw it as hunting territory, as farm land, as bushveld that should be settled and subdued. Our attitude is now less extractive, more preservation, and of course it helps that tourism can be made to pay. But threats remain: poaching, mining, climate change. Fortunately there are dedicated individuals working to see that Arcadia lives on.

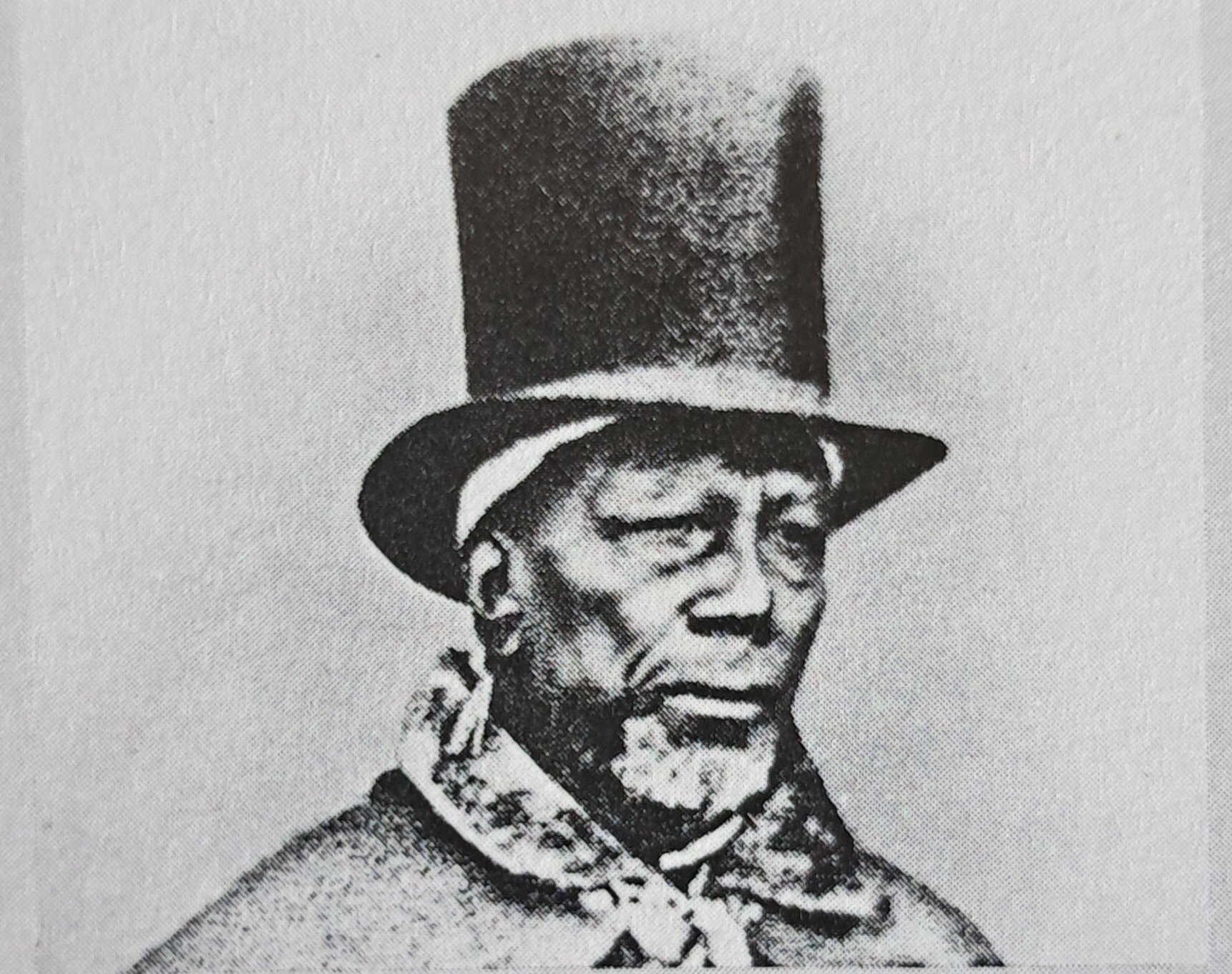

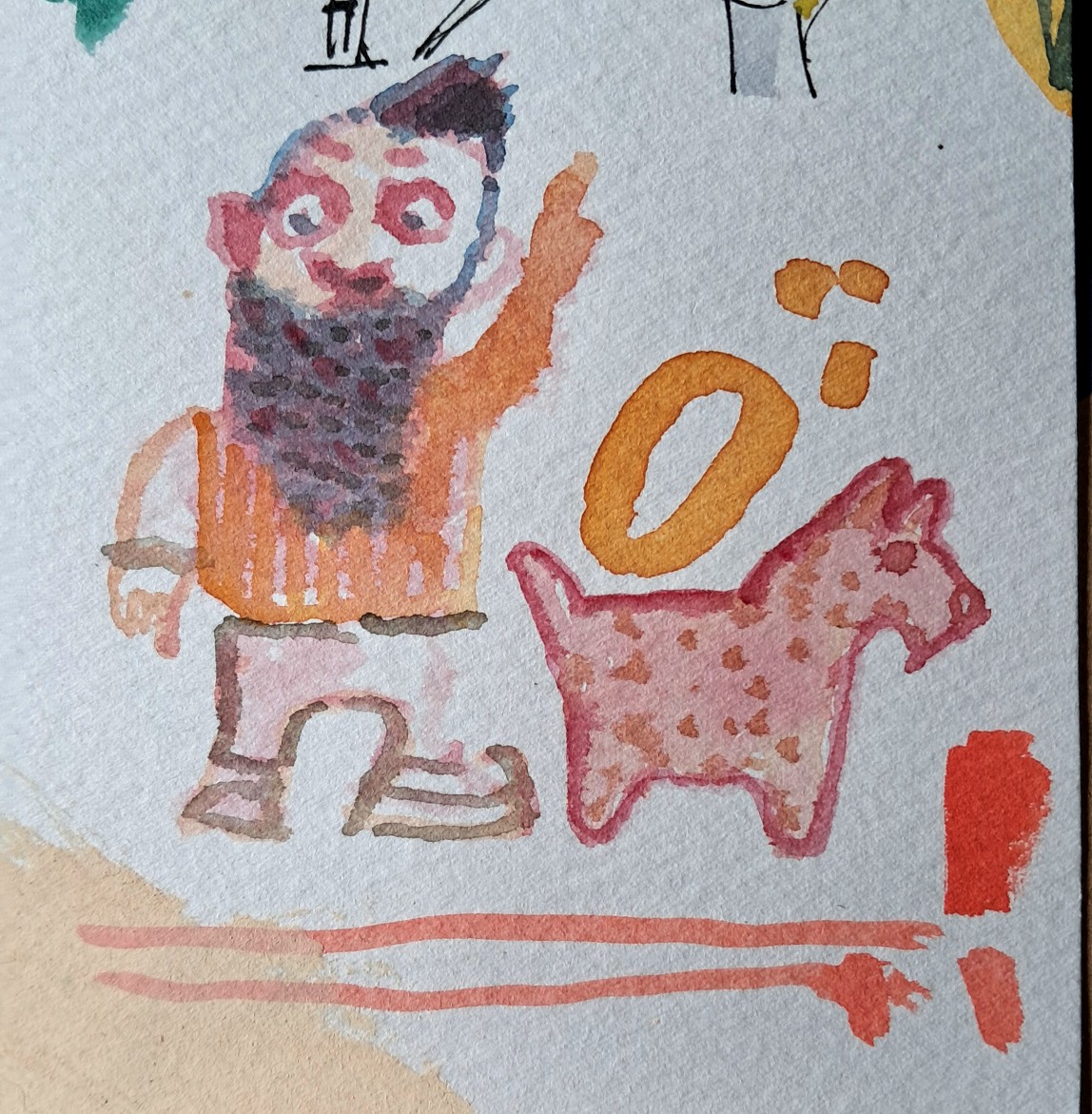

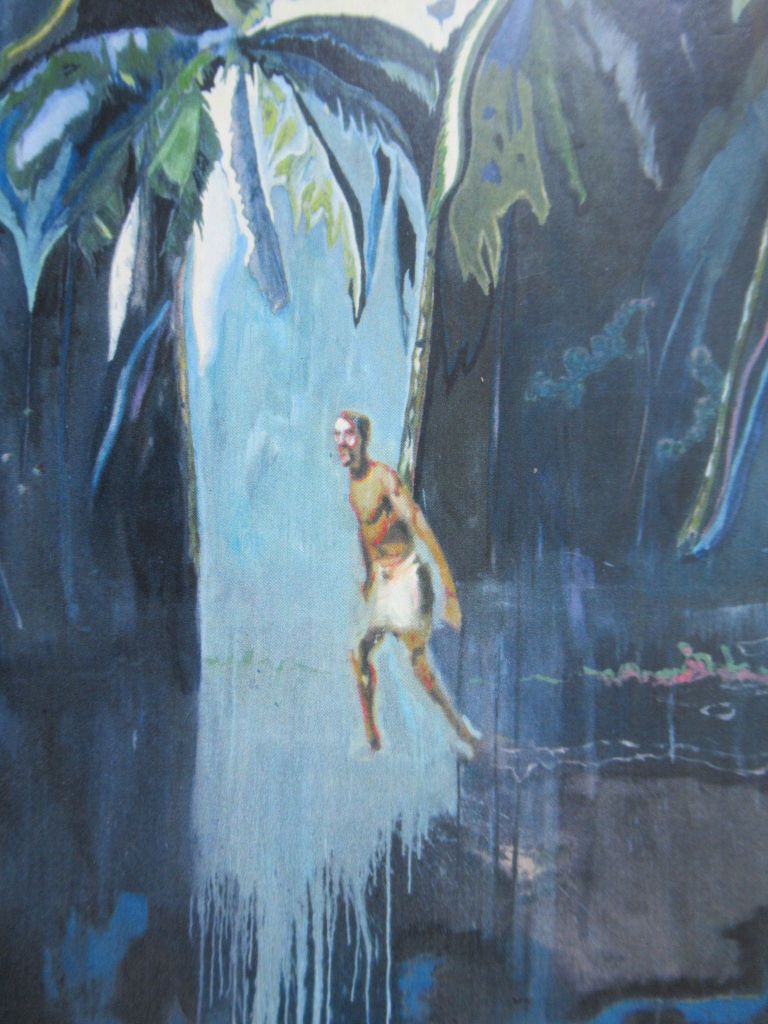

Lion attack illustration by the great CT Astley-Maberly. From Harry Wolhuter’s “Memories of a Game Ranger.”